Choose Your Preferred Interface

Blåhaj Lemmy offers multiple frontend interfaces. Select the one that suits you best!

(hint: mouse-over the images to see the light/dark themes)

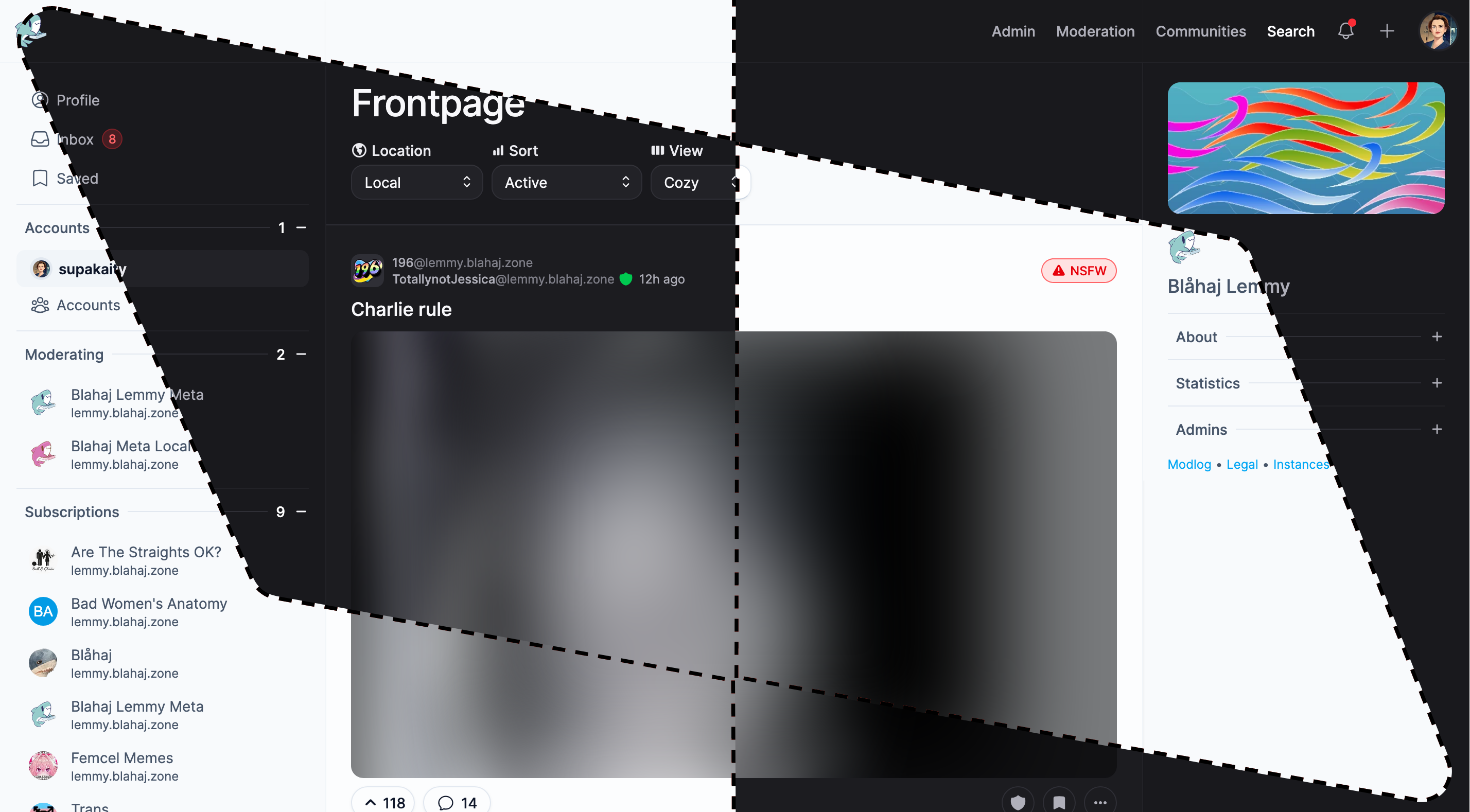

Photon

A sleek, modern interface with a clean design and smooth animations

mlmym

Old Reddit style interface - familiar and functional

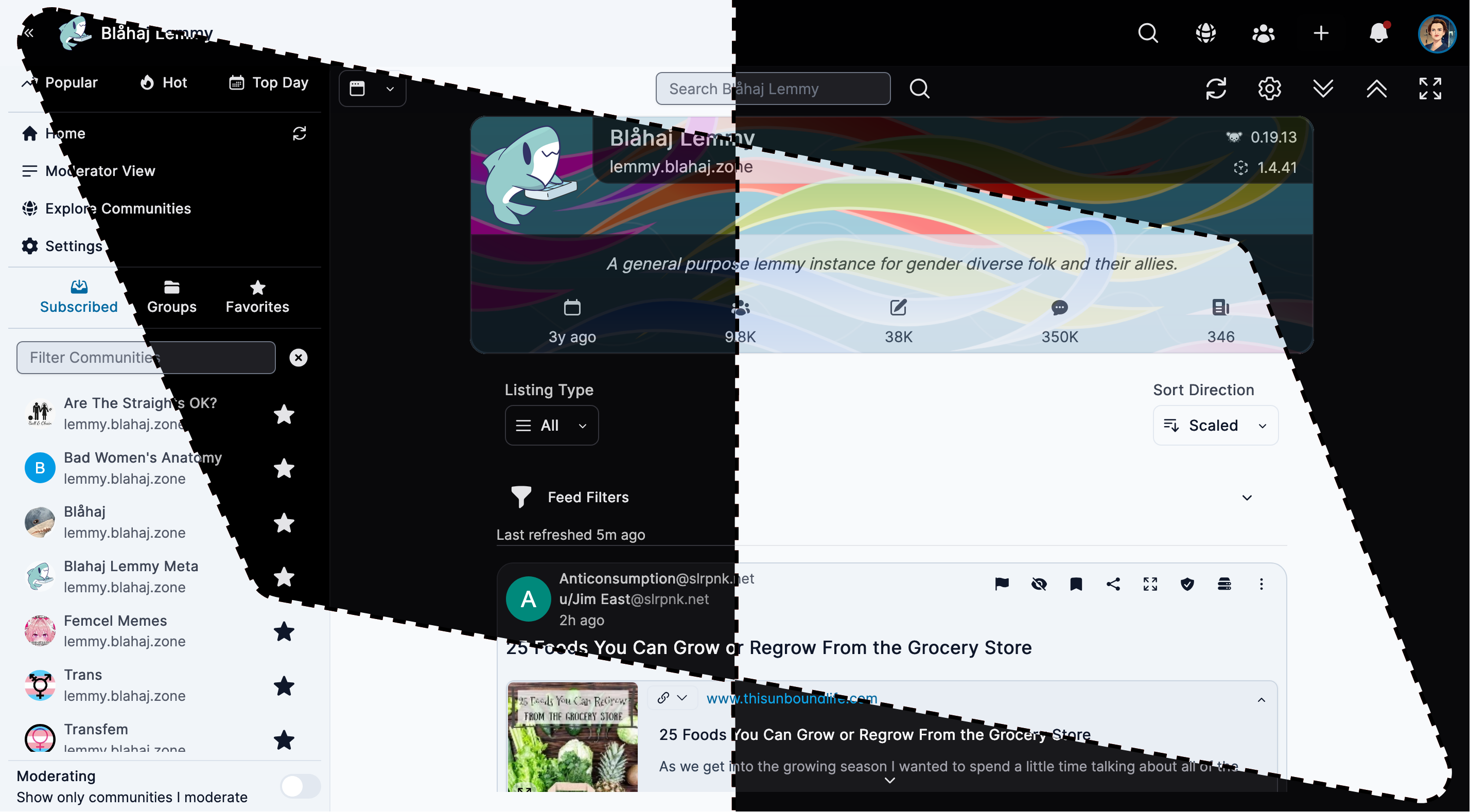

Alexandrite

A beautiful, desktop-focused interface with powerful features

Tesseract

Feature-rich interface with advanced moderation tools

Blorp

Modern Threadiverse client for Lemmy & PieFed with native apps

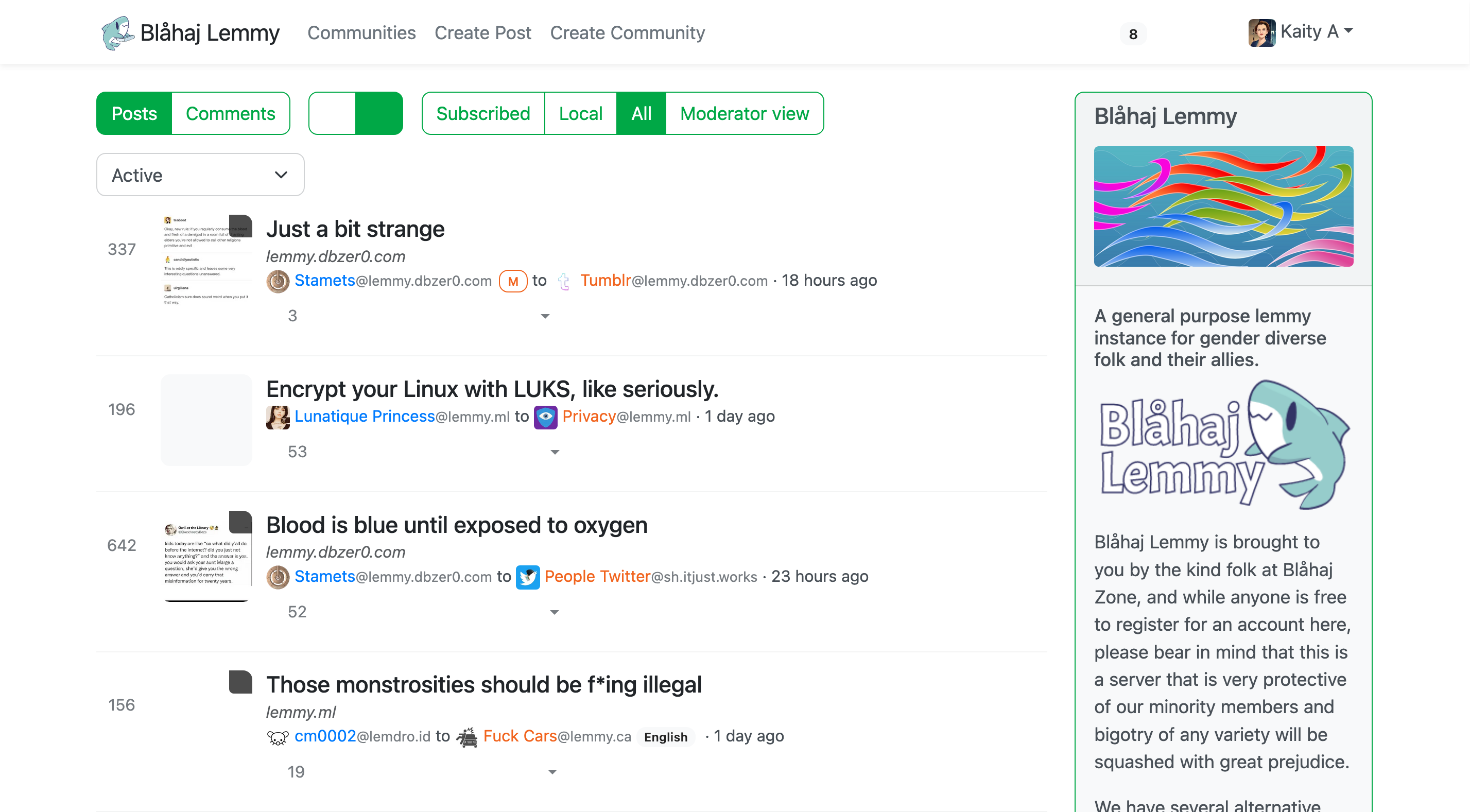

Lemmy UI

The default Lemmy interface - simple and straightforward

Current saved preference: